All information which could lead to the identification of this story’s protagonists have been modified given that, even though this story is about no one, it would seem as though we should keep ourselves from harming anybody’s reputation.

Closed meetings and procedures

A desk.

A ton of binders and filing cabinets.

Two women.

“You know that the accusations you are bringing forward are very grave and that we cannot begin procedures if you are incapable of proving the veracity of your allegations.”

The person we will call Melanie tightens her grip on the orange envelope which contains all the information she deemed necessary to prepare herself for this meeting. You can tell by the crumpled edges that she had been hanging on to it for quite some time already. She is sweating, but doesn’t take off her coat. The guidance counselor seated across the desk busied herself while she spoke those words. She arranges the papers which she carefully lays on a pile of folders and ends up slowly crossing her fingers while looking at the young 22-year old woman.

The obvious sympathy that Marlena had for her no longer seemed to hold. The formal tone of voice she had adopted instead of her usual friendliness had rapidly established the singular character of this meeting. Still, she dared to bring up Bertha and Haryana. Those who had, just like her, given up a year early.

– “You know that I cannot provide information on other students’ files”, Marlena cut her off.

– “But…” Melanie tried.

– “If you would really like to mobilize the other girls which ‘you claim’ were also victims of harassment so they might testify in your case, it will be up to you to reach out to them. In the event that you should choose to carry on with the complaint you are depositing today, you will have to start by meeting the general director and M. Bachand to clarify the situation. I will give you a list of resources that could help you along the way. Afterwards…”

And the silence persists

“No fucking way I’d go meet him! And with the general director on top of that!” exclaimed the young woman, as she grabbed the black Russian she had just been served at the bar of the downtown hotel where she works as a cook. Having just finished her work shift, her shirt completely flared and ringed with two large halos, a heap of hair and netting framing her half-shaved head, she would not be the first to have given up on her complaint ahead of the difficult task of following the procedures required by the institutional channels of denunciation. A 1995 study reported by the Public health expertise and reference centre (Institut national de la santé publique du Québec, or INSPQ) indicates that only 10% to 20% of workplace sexual harassment victims denounce what happened to them to a supervisor or a person in a position of authority[1].

Recently, the Inquiry into sexuality, security and interactions in university spaces (Enquête sur la sexualité, la sécurité et les interactions en milieu universitaire, or ESSIMU) lead in 2016 by Manon Bergeron, professor at the Department of sexology at UQÀM and Sandrine Ricci, co-investigator and lecturer at the Institute of feminist research and studies (Institut de recherche et d’études féministes, or IREF) found that the culture of silence that surrounds sexual harassment in academia remains unaddressed. Indeed, only 9.6% of respondents having experienced sexual violence have filed a complaint against their aggressors to their university boards[2].

Beyond a common definition, a mutual understanding

The notion of sexual harassment has evolved over the past fifty years. Today, the phenomenon is legally recognized and its’ definition is much more precise than it was at the time. According to code of law 81.18 from the Labour Code, psychological, physical or sexual harassment consists in “any vexatious behaviour in the form of repeated and hostile or unwanted conduct, verbal comments, actions or gestures” which answers the four following criteria: undesired, affecting a person’s dignity and/or psychological or physical integrity and ultimately results in a harmful work environment, in this case the school or internship environment[3].

Despite all of this, the main reason invoked by the participants of the ESSIMU study to explain their silence was revealed to be that, when they choose to deposit a complaint, they do not perceive the entire nature or gravity of the acts perpetrated against them.

“He asked me to come into his office to discuss an absence without cause. I did realize something was up. At the time, I wasn’t certain. You know, some people just don’t have the same personal space as you… it’s normal for them to be two inches away from your face.”

On top of that, with the 2005 education reform which removed courses on personal and social training from the curriculum, academic institutions have quietly rid themselves of their roles and responsibilities in providing sexual education for youth. Until very recently[4], all we had to this effect was a guide intended for teachers: Sexual harassment in academia – Implementation of our policy – Seeing, preventing, counteracting[5].

Is it then surprising to hear young women like Melanie minimise the violence done against her?

Silent, with eyes wide open

The recent cases of sexual harassment denunciations in the québécois cultural sector, most notably those of Gilbert Rozon and of Éric Salvail, demonstrate the expediency with which institutions rid themselves of their employees once the silence is broken. Rattled by our own surprise, we bear witness, we fill the public stage with our empathy for victims by calling out loud and clear, no less rattled, the silence that entraps them.

This hypocrisy is something that Melanie calls out as well.

– “This asshole has been doing that for years!” she tells me.

Her eyes fall upon the black line at the bottom of her glass as she swirls the ice within. Bertha and Haryana were already relating how Anita had let go of her course little by little, to never return.

Talking about sexual violence in academia implies asking questions about the power relations that structure our work relations within institutions of education. An important part of these situations, nearly a third (30.3%) to be precise, occurs within the context of a hierarchical relationship, a fact which is probably not indifferent to the muffled murmurs that cover them up[6]. On top of that, it appears as though individuals who identify as women or as members of gender minorities as well as disabled and foreign students are more likely to be affected by sexual violence, while it is a vast majority of men that we find on the aggressors’ side. It is therefore impossible for us to discount the feminist perspective and an intersectional framework if we truly seek to fight back against the culture of violence in which students are immersed and which constantly trivializes, reinforces and maintains pre-existing power relations, most notably those between teachers and students.

But why didn’t you say anything?

What Melanie bemoans the most is the burden of proof. The burden of shedding light on violence that is not hers. It is written that “in all cases, the victim will have the burden of demonstrating the violation of their dignity or of their psychological or physical integrity”[7].

Melanie is, in the eyes of the law, responsible for the violence done to her.

– “So, did you quit the program?” I asked her, rather stupidly.

She took a drag from her cigarette, hesitated. The glow of an old lightbulb danced on her face while she dipped the tip of her foot in a puddle in front of the anonymous front door of a building in the Old Port.

-“The girls, they’re all willing to talk to me about it, but not to go to court… I know that I should”, she told me, feeling a bit guilty.

Far from wanting to add unto the responsibilities already weighing down on her, I knew she wasn’t wrong. The amplitude of recent denunciations from the #MeToo movement had already pushed the government of Quebec into attributing an extra million dollars to the organizations dedicated to helping victims of sexual assault and harassment[8].

– “However, I still have a good job, I make good money… I don’t want to get into it.”

Melanie is a part of those 29.8% fo people who have suffered sexual violence in the context of their training and that, silent, would rather not think about it and move on.

*

In total, 3430 of the 9284 respondents of the ESSIMU inquiry for a total of 36.9% reported that they had been victim to a form of sexual violence. Whether they were dealing with an insistent thesis supervisor, a teacher with a lengthy reach or an internship supervisor needy for attention, the students find themselves vulnerable and isolated when dealing with the Institution and its’ mechanisms it offers to handle sexual violence. Since they are not recognized as workers, they cannot benefit from the same judiciary or economic leverage that workers have[9]. As for teachers, they can count on the support of their union to defend their position in front of the institution. While a university is a social space for both groups, the importance of defending their jobs seems to be greater than the importance of ensuring that students stay in school. During internships, the situation is just as problematic. The hierarchy and the ambiguous status of interns accentuate their vulnerability to harassment[10]. Often times, the intern is under the authority of a single person in the organization, who has the role of supervising their training and of endorsing their achievements. The student consequently finds themself to be dependent of this person, who should not be displeased so as to avoid compromising their academic progress.

As long as the difference between the status attributed to workers and students persists, the mechanisms of complaints and the concertation tables put in place in academic institutions will continue to be insufficient and inefficient. Students would have more control over their study conditions if they were recognized as colleagues working in the context of a job.

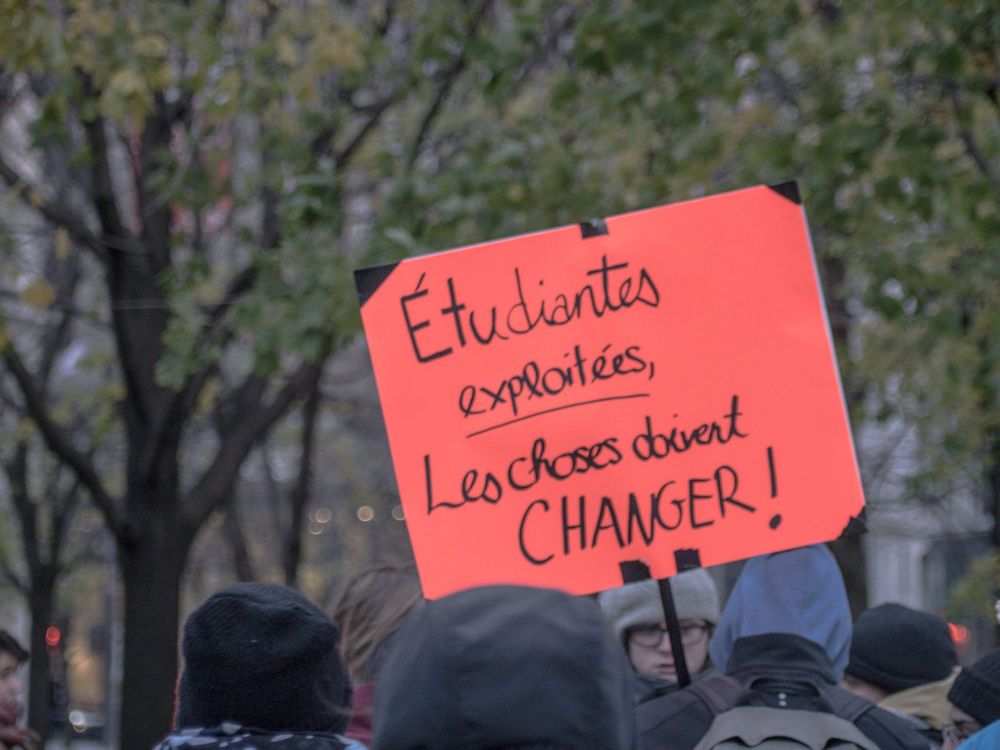

It is in this perspective that we demand a student wage as a political strategy that would help modify the power relations within academic institutions by ensuring that students would not only have control over their working conditions, but also have legal leverage with which they could mobilize and organize collectively against sexual assault.

We must organize as workers!

By Katherine C-P

This article was published in the Winter 2018 issue of the english edition of CUTE Magazine.

-

FITZGERALD, L. et SWAN, S. (1995). Why didn’t she just report him? The Psychological and Legal Implications of Women’s Responses to Sexual Harassment. Journal of social Issues, 51 (1), 117-138 ↩︎

-

BERGERON, M., HÉBERT, M., RICCI, S., GOYER, M.-F., DUHAMEL, N., KURTZMAN, L., AUCLAIR, I., CLENNETT-SIROIS, L., DAIGNEAULT, I., DAMANT, D., DEMERS, S., DION, J., LAVOIE, F., PAQUETTE, G. et S. PARENT (2016). Violences sexuelles en milieu universitaire au Québec : Rapport de recherche de l’enquête ESSIMU. Montréal. Université du Québec à Montréal. ↩︎

-

https://www.cnt.gouv.qc.ca/en/interpretation-guide/part-i/act-respecting-labour-standards/labour-standards-sect-391-to-97/psychological-harassment-sect-8118-to-8120/8118/index.html It should be noted here – and I will get back to this – that academic institutions have drawn upon this definition, but are not subjected to it. Each establishment therefore possesses its’ own procedures and denouncement channels. ↩︎

-

http://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1073006/education-sexuelle-obligatoire-eleves-septembre↩︎

-

http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/references/publications/resultats-de-la-recherche/detail/article/le-harcelement-sexuel-en-milieu-scolaire-implantation-dune-politique-voir-prevenir-contrer/↩︎

-

In total, a little more than a quarter of respondents (25.7%) have witnessed or been confided with situations of sexual violence in academia. ↩︎

-

https://www.cnt.gouv.qc.ca/publications/chroniques/articles-rediges-par-des-specialistes-de-la-cnt-pour-des-revues-externes/le-harcelement-sexuel-au-travail/index.html↩︎

-

http://plus.lapresse.ca/screens/d83085ab-d661-44c4-82c7-08ae31498a04__7C___0.html↩︎

-

In France, labour standards were modified in 2013 to extend the protections given to workers so that they would include interns. ↩︎

-

For more information (french source): http://www.huffingtonpost.fr/2017/11/09/paroles-de-stagiaires-les-victimes-les-plus-fragiles-du-harcelement-sexuel-au-travail_a_23271715/↩︎